35 Anniversary – Everest West Ridge

One of the clasic Himalayan problems

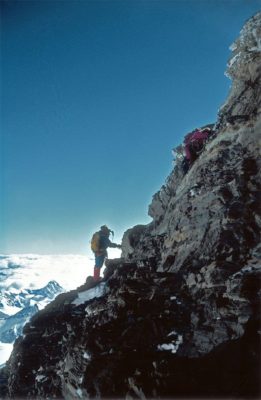

CLIMBING ON THE EDGE OF POSSIBLE

There are no mountains in the world like the Himalayas. Thousands of its peaks are higher than the highest Alpine summits, and hundreds are higher than the highest mountains of the Andes or the Pamirs.

And of course one is higher than all others – Mount Everest, King of the Himalayan giants. At one time an ascent of Everest was considered an extreme achievement of human endeavour. When Everest was conquered, many people

wondered what would be man’s next great target, since there is nothing higher to climb. Still, one can try to climb the same mountain using more difficult routes!

This is the story of our ascent of Everest via the west ridge, unconquered before 1979. There have been many attempts on the route, and many accidents; it could be described as “Clasical Himalayan Problem”. It has always fascinated climbers, but expeditions have frequently been dogged by failure and tragedy.

Most Alpinists would regard climbing the highest mountain in the world as fulfilment of their sweetest dreams. I was reluctant to think that I might reach the summit simply because I had been chosen, but even to participate in a

Himalayan expedition is a special honour for any climber, especially for an attempt on the highest mountain in the world, and moreover via a hitherto unattempted ridge.

The 1979 Everest expedition consisted of 24 climbers, 2 doctors, 3 reporters and 20 Sherpas.

Over a period of 19 days, 750 local porters carried 18 tonnes of equipment up to a height of 5300 metres. Tone Skarja, an experienced Himalayan climber, was the expedition leader. On the Khumbu glacier we make a complete village of tents, forming the base camp at 5300 metres. From here the route leads via steep cliffs to the saddle

of Lho La at 6000 metres.

Only 83 people have climbed Mount Everest, from various directions, before 1979. Most took the southern route from Nepal used by the first British expedition with Edmund Hillary and Norgay Tensing in 1953, via the south saddle and on to the south face. The west ridge involves an extremely long climb, and is exposed to

powerful winds from Tibet. And no-one knew of a certain route over the final section, the steep yellow belt.

Logistics for the expedition via the west ridge are a story of their own. We have to carry 6 tonnes of food and equipment up a very steep rock-face to reach the saddle of Lho La, which would scarcely be possible without the help of the Sherpas. The expedition has already used more than 10 kilometres of rope on the mountain, 300 metres of rope ladder, 50 metres of rigid aluminium ladder, 40 tents, 80 sleeping bags, 500 ice screws and pitons, hundreds of litres of kerosene and gas for cooking and several tonnes of food for the climbers and Sherpas. From all of this, each climber who manages to reach the summit will be carrying just six or seven kilograms!

Each day, more of the load is moved from base camp to Camp 1 on Lho La saddle. The climbers take turns to go ahead and secure the route, and in doing so begin to acclimatise to the rarefied atmosphere. These cycles of acclimatisation tie in well with our progress up the mountain and the secure ropes are invaluable for a safe descent to base camp for rest.

We have a daily battle with icy slopes, low temperatures and strong winds, but within about twenty days we have established five high-level camps, the routes between them secured by ropes. The expedition’s greatest problem awaits us after Camp 5 above 8200 metres where Viki Groselj and Marijan Manfred were trying to find a route to the summit itself. Manfred and Groselj had nevertheless contributed vitally to the expedition’s success by fixing ropes and enabling others to reach the summit. At the start of the expedition no-one, least of all I myself, had counted on my being a candidate for the summit. But during five cycles of acclimatisation I had no real problems with the height, and I began to think of my wish to reach the summit and to wonder whether it might be possible.

After 40 days of strenuous toiling and climbing, Nejc Zaplotnik and Andrej [tremfelj had the satisfaction of reaching the summit. Just one day behind them, another group prepares for the summit in Camp May 14th 1979 dawns a beautiful day. Each person advances over the last 700 metres towards the summit carrying two bottles of oxygen. We follow the cliff to below the Grey Jump, where Nejc and Andrej had passed two days earlier. We avoid some difficulties at 8600 metres using a route via a very steep face which no-one had crossed before. We seemed to be at the limits of human capability while climbing the last stony wall, just 150 metres below the highest summit in the world, which nevertheless draws us with magical power.

The moment of stepping onto the highest in the world is one of unimaginable happiness. Being the highest man in the world is a complete reward for all the risks and effort which came before. But this is also the most critical moment in a climber’s life, because he has now covered only half the necessary distance to arrive back home. The more dangerous half of his journey is his descent to the foot of the mountain. The moment of standing on a summit distinguishes this sport from all others. In other sports, a competitor makes a decisive, winning move, the referee blows his whistle, or a tape is broken at a finishing line and that is the end of the competition. After the match he goes to a warm changing-room and takes a shower. But when we reach the summit of a mountain, a second trial is about to begin, in which one’s life is at stake. A terrible storm is brewing over Mount Everest. The wind blows at 150 kilometres per hour and the temperature drops to minus 40 degrees.

The following morning, after surviving the night at 8400 metres in the open, Ang Phu slipped and fell 2000 metres down the Ronbuk glacier.

For myself, having survived, Mount Everest remains a most beautiful memory, a success which can perhaps compare with winning a Grand Slam. But a Grand Slam is played every year and someone must win. Here, apart from the fact that a man rarely wins, he can also die. A climber must really be a little crazy to tackle something so challenging; but not so crazy that he allows himself to come to grief.